As the world mourns Everest’s deadly toll, why isn’t any one asking about the chances for a good life for the Sherpas completely outside of climbing?

By now the grim tale has traveled from a few thousand feet below the rime iced summit of Mount Everest to middle America, National public radio, and just about everywhere in between. Days ago, an horrific avalanche claimed the lives of 16 local guides, mostly ethnic Sherpa, fixing ropes for the upcoming weather window of May, when most attempts transpire. Amid the horror, the entire climbing season hangs in limbo. Sixty years ago, when two men stood together on the summit of Mount Everest, the entire world shone brightly beneath their feet. After their achievement both became household names, one knighted and immortalized on his nation’s currency (among other accolades); the other worshipped as a living deity, himself festooned with medals, including the lofty George, from Queen Elizabeth II.

Know which was the humble son of a Himalayan yak herder? The latter, Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, 11th of 13 children, made it to that crystalline viewpoint through pure grit, big-hearted valor, and a bit of luck, having made it within 750 feet of the summit once before, and having helped “Ed”, as he was called, out of a crevasse in the days before their ascent, cementing his already deserved spot on the summit bid. His joyous achievement was famously photographed by Hillary and, maddeningly, picked over by nationalistic fussers for years as to which man was “first”.

What did a meter or two ahead of the other matter after their slow motion ascent to the top of the world? The distinction is more or less meaningless—neither could have made it alone, and the two had a gentleman’s agreement to hide the order in which they stepped through the snow along the summit ridge. Hillary, a gentleman of uncommon class, declined to identify who was “first” until after Norgay passed away, maintaining its irrelevance. Along the way, the Sherpa people, illuminated by Norgay’s ‘Tiger of the Snows’ triumph, became a potent symbol.

Trouble is, that symbolism still obscures true summits of Sherpa culture.

While it is undoubtedly true that Norgay’s climb in the -50C wind-chill propelled his people widen their deserved reputation as trusty, selfless, incredibly talented climbers, it also locked the word Sherpa into a kind of anthropological cul-de-sac, where altitude, avalanche, and death-defying rescues are all there is. But thanks to the inspiration of Norgay’s inspiring feat, there are also Sherpas who get to high altitude by piloting 767s and who live in cul-de-sacs, chasing another goal: The American Dream. There is life beyond Mount Everest, and some Sherpa have been pursuing it in ways that those who would prefer to think of Sherpas as brave mountain servants might find shocking.

One night almost exactly ten years ago, as a relative newcomer to New York, I was with a former colleague from National Geographic Adventure magazine standing in Lahore, a SoHo takeout restaurant popular with cabbies, waiting for hot, sweet chai tea. We were talking about mountains we hoped to visit in person someday, including Mount Everest and K2, when a small voice behind us spoke up.

“You guys climbers?” asked a compact man with slightly wary eyes.

We weren’t, at least not seriously, but he certainly was. The story of what happened next became my personal mountain climb, a years-long reporting project resulting in a short item in The New York Times metro section, and, later, a substantial feature in Outside. It turned out that Tsering was, like everyone else in Lahore that day, an immigrant from the Himalaya, and, improbably, a NYC cabbie. But unlike the others, he was also a grand-nephew of Tenzing Norgay, grew up in Darjeeling in the famous Norgay home, Gang-La, had two degrees, a loving wife, and two beautiful children. His home was filled with mementos—given to him by Tenzing himself—of the glory years of Everest exploration. He was practically Himalayan royalty. But he had left it all behind to try his luck in America, and, like many Sherpa, was soon guiding Gothamites around the steel peaks of Manhattan. What I learned from Tsering, his fellow Sherpa cab driver- and odd-job buddies, and the many climbers I spoke to, is the true meaning of Sherpa pride, the wellspring from which it comes being deeper and far more ancient than a single climbing expedition in 1953. As the climbing world picks over accounts of this accident, and, just last year, a terrifying brawl on Everest between climbers and Sherpa brought on by a slight—it could all take years to sort all this out—today is a good day to remember that Sherpas aren’t just brave climbers. They are citizens of the world capable of absolutely anything, and the brave men who died fixing ropes in the Death Zone knew it, which is why their huge list of demands should come as no surprise. Breaking the enduring archetype of climber’s assistant may be impossible. When I reported this story in 2007 for Outside, Sir Edmund Hillary told me he saw clear dangers in Sherpa leaving the Himalaya for America. “I know a lot of Sherpas are now based in New York, and that’s fine,” said the climber, then 87, “but I just hope that they don’t completely lose their culture.”

“Going to work somewhere in New York, or anywhere in the U.S., would be very, very tempting,” Hillary continued. “The only thing is, for every Sherpa who goes to New York and earns money and sends it home, the vast number are good people who are really needed in the Khumbu. I’d certainly hope that they all come home, because they have so much to give to their own communities.”

Tsering, focused on a better life for his family, saw things differently. “My life is already burning now. I am like a candle. But the light which the candle gives is going to be good for the coming generations, which I can see in America.”

The postscript to my this story about Tsering and his Sherpa friends working toward a better life in America, including multiple Everest-summiteers Kipa and “Speed Kaji” Sherpa, is one I sometimes have trouble believing myself. As I reported the piece, I learned the New York based Sherpa—some 1,500 of them—were organizing to try to bring His Holiness the Dalai Llama to New York for a teaching at Radio City Music Hall and, at the same time, raise a million dollars to build a Sherpa cultural center in Queens. At press time they were up to $426,000 and gaining steam.

The Sherpas kept going. So did I.

One day in 2008 I got a call from one of the cabbies. They needed help, he said, for something important. “The Dalai Lama is really coming,” said Galgen Sherpa, Tsering’s close friend. “What do we do about press?” To my amazement, by driving taxi and working their various odd jobs—now you know what your Sherpa cab driver may be chatting about on his cell phone—the Sherpa had raised several hundred thousand dollars to bring HHTDL to New York. Though he’s not an elected official, he’s accorded the same protection as heads of state by the U.S. State Department, who, Galgen explained, I would need to coordinate with. Floored, I agreed.

A short time later, in a ground floor apartment in a leafy corner of Woodside, three Sherpa gathered to put the finishing touches on preparations. “We are working on the decorations now,” said Galgen, who hosted the meeting. “I think we are gonna go with 1-800-FLOWERS,” he said.

In addition to decorations there were more pressing matters; a fourth cohort joined proceedings by phone, and, with a DVD of their spiritual leader lecturing placidly on a silenced 46” flatscreen, two laptops, an iPhone, and two PDAs blowing up every few seconds, the men got to work. “Let’s make it happen,” Lobsang Thinley said, known to his friends as “Salaka”, another key organizer who’d just come back from a backpacking trip.

Suddenly the room erupted with urgent chatter in Nepalese. Tenzing Ukyab, also a Sherpa, and Lobsang, couldn’t agree on what to say in a press release about China, if anything. “We’re non-political,” urged Galgen. “Let’s just say, we are in support of the Dalai Lama’s aspirations,” said Tenzing Ukyab, who was taking time off from his day job selling handicrafts from his homeland inside ABC Carpet & Home. Salaka solemnly agreed, and the matter was tabled. “This event is only possible for us because we live in a free country, in the U.S.,” said Galgen.

It had been something of an improvisation, but a wildly successful one, considering their whole planning-visits-by-world-leaders record: one U.S. attempt, one success. The Dalai Lama had been booked to appear on July 17th 2008, before 5,900 spectators; through donations and ticket sales, the men recouped $325,000 in expenses, raised mainly from members of their community. Not bad for a bunch of cabbies.

Organizing that press access to the Dalai Lama’s appearance in July of 2008 necessitated a lot of emailing with said officials (vetting and background checks which were coordinated with The Tibet Office, the Dalai Lama’s cautious political arm). There was one final trip to a restaurant in Queens, Himalayan Yak, where, on the eve the teaching, Galgen, Salaka, and some 25 other Sherpa were rushing around in a pre-wedding night-like state of emotion.

Just as I was thinking about leaving to get some rest around midnight, Galgen approached me. He wanted me to go and greet the Dalai Lama at La Guardia in a few hours, joining the inner circle of visit organizers. Touched, but reluctant, I protested—this was their Everest—but he and the others wouldn’t hear otherwise. I was going. Sleep? Forget it. I headed home, excitedly emailed Elizabeth Hightower, my editor at Outside at 4:32AM, put on a suit, and jumped on the subway, headed for Queens.

We met around 6 in the bright, humid, hazy morning on a street corner in Jackson Heights, seven Sherpa and other Himalayan Community organizers in a couple of slightly banged up, but just-washed, town cars. They’d dressed for the occasion, one wearing a crisp beige cowboy hat, as they do at times. We were guided to a hangar area on the tarmac, where several aviator-clad State Department officials were preparing a long motorcade—with eleven other cars—inspecting each one for bombs using pole-mounted mirrors. A tight-lipped agent briefed us with the clipped diction of a military commander: “No photographs. Keep it tight, keep close and fast, and whatever happens, do not get separated in traffic.” Wait, what?

We weren’t just there to wave hello, we were going to be driving in the motorcade with the Dalai Lama. Suddenly the State Dept. guys signaled. Lined up, we raced across a tarmac, parked in an elliptical formation. This was just practice—or a safety measure?—but after several breathless minutes of waiting we raced off again to another spot, each time forming our perfect 13-car line. The anticipation was starting to get to the Sherpas, and me too. What was this, Clear and Present Danger?

When, moments later, we got the signal, we raced to our third and final spot, timed to meet the small jet as it rolled to a stop. The door opened, and out popped the smiling face of The Dalai Lama, squinting in the light. The Sherpas were coming a little unglued. “What do we do?” I wasn’t sure what the tough-looking agents would do, but I decided they had to take a chance. “Get out—Go and greet him!”

As he descended the plane’s stairs, the State Dept. guys were pacing around, finger-on-earpiece style. Out of the car now, I stood just off to the side as the Sherpas rushed forward and embraced the Dalai Lama, placing the ceremonial silk kata scarves around his neck, clasping hands with his and bowing in a state of bliss. They regard this man, after all—just as Tenzing Norgay had been worshipped by some—as a living reincarnation of Buddha.

I stayed a step back from the receiving line to observe, and suddenly we were whistled back into the cars. There was a lead Suburban, armored, with the Dalai Lama and his assistant behind it in another bullet-proof town car with very tinted windows.

As the Sherpas vibrated in shock, having just met their hero—I was completely awestruck as well—we were, for lack of a more polite phrase, hauling ass across the runways of La Guardia. We sailed off the tarmac and through a stoplight at full-speed. We really couldn’t believe the next part: The Grand Central Parkway and Long Island Expressways had been blocked off so the motorcade could drive on an empty freeway for miles approaching Manhattan. The Sherpas had, effectively, shut down an entire segment of New York City, for their guest. The two agents who’d briefed us popped out of the windows of the lead vehicle, brandishing assault rifles and darting their heads around, looking for danger.

We did not get separated. And for all Manhattan knew, we had the President of the United States on board.

The rest of the day went smoothly, at least inside. The stage had been beautifully prepared, with monks seated around the brightly colored, padded speaker’s perch. I stood around backstage and mustered the confidence to chat with the Dalai Lama’s personal liaison from the Tibet Office, Tashi Wangdi, who dryly informed me it would take six months to apply for an actual interview. The actress Uma Thurman’s father, Robert, introduced the guest of honor. Meanwhile, outside, around 100 protesters and an estimated 500 audience members clashed sharply enough to warrant intervention by mounted police.

After the teaching, the Sherpa and other Himalayan organizers gathered to the side of the stage. As I snapped the last group shots of the day with the Sherpas, assorted monks, and their hero, the State Dept. guys revving up outside, I was grateful. There was no more to do but go home. Joyfully, assuredly, the Sherpas had guided me, too, to a view like no other. And now they’re organizing to help support the stricken families in the Khumbu even as they keep working for progress here. “We all know about the risk that come with this [climbing] job, but due to lack of other opportunities, we have to take on these task and earn the livelihood,” Galgen wrote me recently. Perhaps it will always be so: the Sherpas’ dreams of liberation, and Everest, linked by a frayed, fixed rope of family, danger, and destiny.

Further Reading: The End of the Everest Myth, by Katie Ives, in Alpinist.

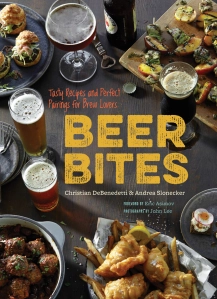

pale gold to pitch black, can lend fruitiness, sweetness, bready flavors, even notes of coffee, chocolate, and soy-like umami. Hops provide bitterness and aromas (from pine tree to orange peel) that are a major part of the beer’s overall flavor. Yeasts add spice, aromas, aftertastes, acids, and of course help create the alcohol left behind during fermentation. Carbonation and grain tannins help “scrub” the palate. Take almost any food, and there’s a beer style that can match it. Baby back ribs with burnt orange glaze, anyone? How about buttermilk-fried oysters and kriek-braised pork sliders?

pale gold to pitch black, can lend fruitiness, sweetness, bready flavors, even notes of coffee, chocolate, and soy-like umami. Hops provide bitterness and aromas (from pine tree to orange peel) that are a major part of the beer’s overall flavor. Yeasts add spice, aromas, aftertastes, acids, and of course help create the alcohol left behind during fermentation. Carbonation and grain tannins help “scrub” the palate. Take almost any food, and there’s a beer style that can match it. Baby back ribs with burnt orange glaze, anyone? How about buttermilk-fried oysters and kriek-braised pork sliders?